Maybe it would be different if we called them the elders but it seems the wisdom that may come with age (not necessarily, of course) is of little interest to younger people.

A wise Buddhist recommends that we never tell anyone how old we are for if we do, we will be folded in with the tiresome, the incontinent, the disposable. Friends will start to haul us out of their low-slung cars, whether we need it or not, push us up stairs, recommend all kinds of tedious measures under the rubric “Safe rather than sorry.”

I’d rather be sorry. At least it has ways out: a sunbath, a massage, a walk in the woods. Sorry has only one outlet: self-pity, and above all things that is to be avoided.

I saw a striking example of the just-too-many on my recent visit to Los Angeles when I spent a couple of hours with a dear old friend in her—what do they call it? One of the roosts for old people.

This is a pretty and exceptionally expensive roost, available only to the few who have a large amount of disposable cash. It has the features of a well-run kindergarten: a garden, with gardening tools, gloves and starting plants laid out; a full schedule of activities that includes daily walks en masse, stretching sessions, musical performances and even a chaperoned visit to the library across the street. And the ground floor is pretty, with floral patterns and gauzy curtains everywhere—and not a book or a magazine in sight—or a television. There may be one hidden away somewhere.

The dining room looks like its equivalent in a luxury hotel: white tablecloths on tables set for four and little posies. My friend told me that the food is remarkably good and at the Happy Hour she is able to procure her regular gin martini. That must help.

But she also told me that when she sits down, at random, for dinner at one of these tables, there is little conversation. The healthy-looking elders have lost the capacity to converse along with their memories. The meals pass in silence with a lot of hungry eating to fill the gap.

She took me to her room, a box perhaps fifteen by twelve, about the size of the room we shared in college, with a counter for a making a cup of tea, a bathroom of grab handles, and one window, covered with shades and curtains. I peered through the slats and saw an entryway. Not a tree or a blade of grass in sight.

And this dear friend whose long life has been devoted to the arts, music and theatre has not a shred left of those interests. Not even a daily newspaper or a radio to hear music and the news. No art on the walls, no magazines, no books.

As is usually the case, her son, who lives nearby, is pushing this solution to her long life in a leafy New York suburb where she can imagine that her painter husband, dead for a decade, is about to come in from his studio, where she has many friends, many memories, and much help, where she can play her piano, listen to music, go to the occasional concert, visit with her friends—where she has a life.

Family is not a life.

I argued strenuously and tactlessly against this termination point for my friend who is healthy and clear-minded and one of the few people I know who does not live on a regimen of pills.

But I know how costly, not in money terms but in more important things, staying out of these places (if one can afford them) can be. A woman in my family has found herself solely responsible for her aged mother who lives on the other side of the country and with whom she has a long-running feud. Now she must travel every two weeks to attend to a crisis, upending her own life and her family’s. And this may go on for years.

I guess the only solution is to laugh. Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote a short story in which a well-meaning acquaintance, visiting a friend in an old people’s home, found himself trapped there. After all he was old too.

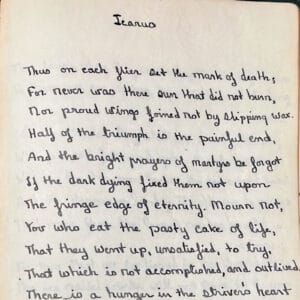

And there are Muriel Spark’s satiric short stories, and Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night/Rage, rage against the dying of the light”—especially when that light is put out prematurely.

Thank you for this

Some good news and some bad news from me: I am in the oldest-old stage and aging in place with some fear and some gratitude.

I am currently re-reading a 1979 novel by Irving Wallace titled “The Pigeon Project”, addressing this subject of longevity in a rather unique way, as only a good writer can do. It discusses the development of a formula to assist in living to perhaps 150 years of age, and the attempt to save it from unscrupulous hands. It then addresses the issues of prolonging life. Interesting novel of an extraordinary situation. My answer to this subject is simple – as the old Reader’s Digest column was entitled – “Laughter Is The Best Medicine.”

Yes, laughter. Real or fake laughter. May I suggest laughter yoga.