From time to time—rarely—when I visit Los Angeles, I pass over its river. I only glimpse it below the furious throughway traffic, torrentious at every hour of the day. There lies the river, under the thunder wheels of thousands and thousands of cars, unobserved, forgotten.

Well, not forgotten, but repressed. A decade ago conservation efforts were aimed at restoring its waters, but those efforts must have run up against the usual obstacles: bureaucracy, competing interests, and lack of funds. Now, as always, the river is not a river but a broad concrete passageway, now and then sheened with a little rain water. There are no paths along its banks, and no reason for paths; no one would want to stroll under those overpasses, or rest their eyes on the dead concrete the river has become.

Probably in the distant past it did contain water, but if so the water would inevitably have become polluted like the rivers and streams of my childhood in Kentucky that stank of sewage, an unbearable miasma in hot weather. Those rivers and streams have been cleaned up but the Los Angeles river remains a concrete strip over who knows what depths of corruption.

So why am I writing about this dead river when further to the north and west there are real rivers, full of living water? There is even the Ohio.

For two reasons: the fence that was constructed two days ago, three feet from the windows of the guesthouse where I’m temporarily roosting, and Harold Pinter’s 1965 play, The Homecoming.

The fence was built with a great racket of hammering and sawing to contain a renter’s dog, not a bad dog but one that would certainly soil the lawn that used to be my view. The view is gone. I’m contained behind the fence and a gate.

Well, so be it. I’m only a visitor and will go home to my own country.

Did I complain to my hosts about the racket and the fence?

No. Because there is nothing more catchable than repression.

Pinter knew this. All his plays, seldom performed now, are structured over and around the violence, emotional and physical, that underlies—barely—the repressions of “normal” families.

The Homecoming immediately betrays its sentimental title in the powerful performance I saw Sunday at the City Garage Theatre, a fifty-seat venue in an old warehouse. Those black box theaters, rapidly disappearing in preference for vast maws that make more money, have always housed what little we have of subversive theatre.

In this play, three brothers, middle-aged, are snarled in a web of mutual hatred of their dreadful old father—their mother is long dead—and become unwitting victims of an act of destruction: the eldest brother brings “home” his wife—or does he hire this woman?—to disrupt repression by seducing all the males in front of him. He is not perturbed by what this woman in her high heels and skin-tight red dress is visiting on his brothers, his uncle, and his father: in the end, he leaves her in this nest of vipers to return to America—freedom.

He explains his detachment: he’s a professor of philosophy at an American university.

In the last lines of the play, the wicked old father is pleading, “I’m not old,” as he approaches the predatory female on his knees. “Kiss me,” he begs.

Sex is what she offers—maybe—in return for her own apartment, clothes, a personal maid. Love is what these silenced, desperate men are desiring, if they even know it. It is certainly not what they will get.

In all ways, this play is a reproach to what has become, with exceptions, commercial American theatre. It runs two and a half hours with a ten-minute intermission; ninety minutes with no intermission is the formula now. It was followed by a “talk back”—the audience given an opportunity to launch their usually misinformed opinions on the cast and director. The director is a woman, widow of the founder. The two teenagers with me, veterans of private school musicals, were stunned.

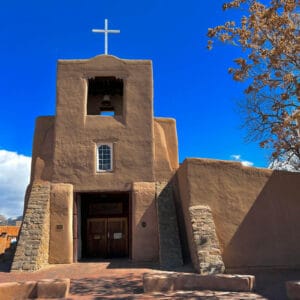

As we exist now in a time of political frenzy, misinformation and over-reaction, perhaps the repression that sits like a lid over nice people will lift a little. It did in the 1960s, then slammed down again. It may be that it takes the violence, implied and actual, of our present regime to shake us out of our apathy. Politically and socially oppressed people may need suffering to crank open the lid and begin to stab at the truths that lie hidden like the buried waters of the Santa Fe River under all families.

Leave a Reply