I don’t know for sure who gave me the set of illustrated boy books when I was ten years old and still spelling my first name Sally. It seems likely that it was my father and even that earlier editions of these lavishly illustrated hardcover books had been his since they were originally published in 1911. I think he might have given them to my two older brothers, which would seem more appropriate, but by this time they were both at boarding school and removed from parental influence except at parent conferences when the emphasis may well have been on Father’s expected financial largesse to the school. Or, in the case of my oldest brother, on some unimaginable transgression of the rules—although he always seemed to escape unpunished.

I don’t know for sure who gave me the set of illustrated boy books when I was ten years old and still spelling my first name Sally. It seems likely that it was my father and even that earlier editions of these lavishly illustrated hardcover books had been his since they were originally published in 1911. I think he might have given them to my two older brothers, which would seem more appropriate, but by this time they were both at boarding school and removed from parental influence except at parent conferences when the emphasis may well have been on Father’s expected financial largesse to the school. Or, in the case of my oldest brother, on some unimaginable transgression of the rules—although he always seemed to escape unpunished.

However they came to me, I’m eternally grateful for they gave me the inspiration for my sense of daring—”chivalry”—that has stood me in good stead my whole life. It never occurred to me to wonder why the women in these novels were so minor, pretty boring presences on the borders of the men’s fighting lives.

These novels were all about fighting, mostly in the crusades or in wars against English invaders, usually French, during the largely imaginary Age of Chivalry when the suffering of the “peasants” (so-called), of women and children, was of little account, except when one of the armored knights leaned down from horseback to bestow a kiss or a coin.

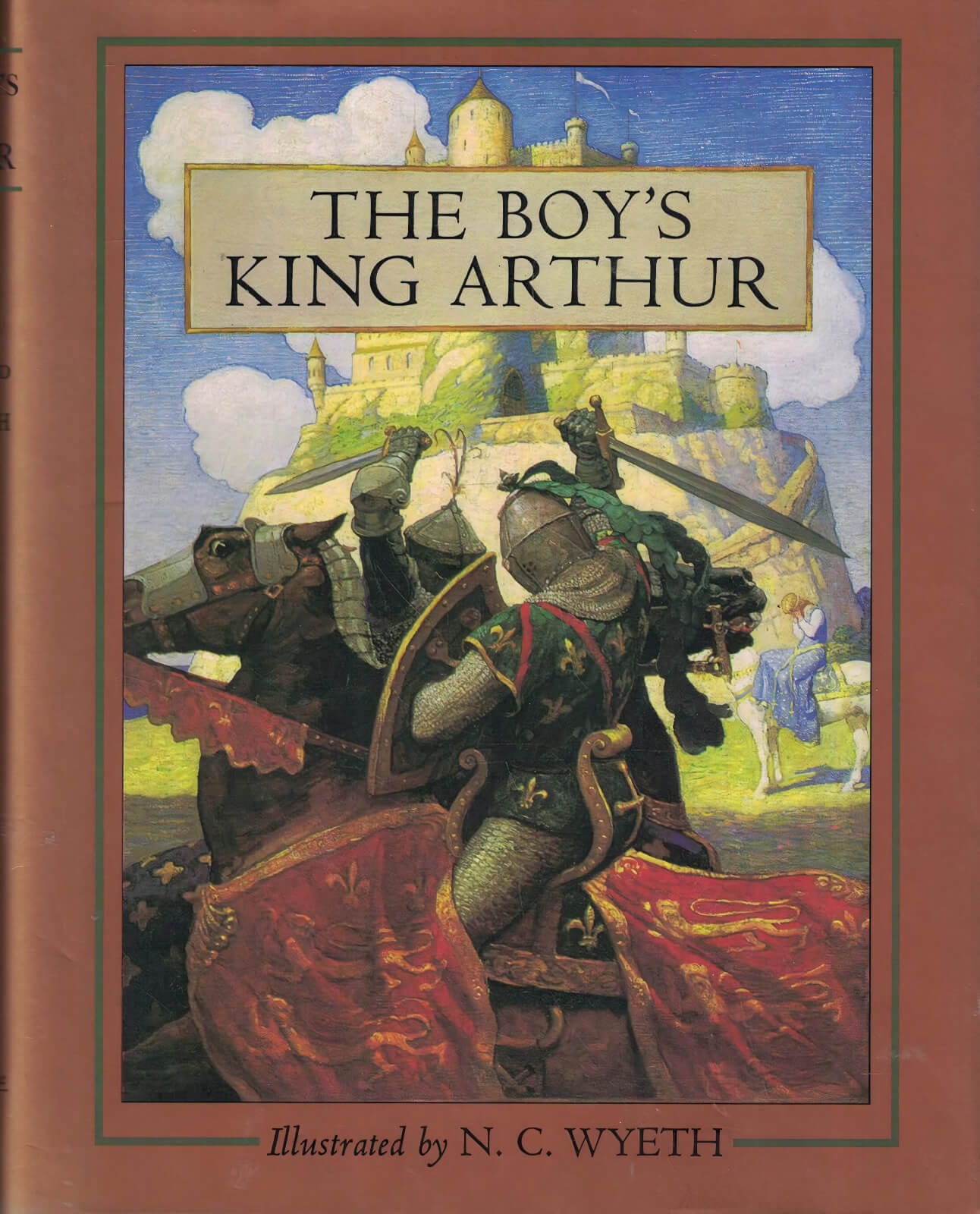

It was the fighting that inspired me. I didn’t notice that “The Boy’s King Arthur”—note the singular—was based on Sir Thomas Malory’s “History of King Arthur and The Knights of the Round Table” or that it was “Edited For Boys by Sidney Lanier”—a well-known poet of the time—or that the illustrations were by the equally well-known artist N.C.Wyeth in this latest edition, published in 1945 by Charles Scribner’s Sons. The volumes must have been bought hot off the press to present to me.

A certain Sir Gilfred of King Arthur’s Court is an example of the unmotivated violence that excited me. Seeing a horse tied to a tree with a shield at its side, “Sir Gilfred smote upon the shield with the end of his spear, that it fell to the ground.” (This pretend Elizabeth speech seemed as normal to me as the Kentucky accents I heard all around me.)

The owner of the horse and shield arrived and was understandably annoyed, and immediately the two knights proceeded to mortal combat. I assume after, the shield was picked up off the the ground, but these novels did not fool with such petty details.

“So they ran together that Sir Gilfred’s spear all to-shivered (“shivered all to pieces”-a translation I didn’t need) and there with all he smote Sir Gilfred and through the shield and the left side, and brake the spear, that the truncheon stuck in his body, that horse and knight fell down.”

It looks as though that’s the end of the impetuous Sir Gilfred, but his assailant took pity on him and took him to the court where “through good leeches” (mistranslated as “surgeons” rather than the blood-sucking worms, maybe to spare the boy’s feelings) “he was healed and his life was saved.” This nobility on the part of winners was an important part of the notion of chivalry.

Why did all this, continued unabated through six more volumes with different knights and different battles, excite me so? I can only guess that in the torpor of my childhood, the clash of spear and shield and the dreadful consequences added a pepper of danger I sorely needed. A few years later when I was given my first horse, I began to supply the pepper myself.

Beyond that, the daring of these knights-at-arms was something I needed in order to grow into myself and fight my own necessary battles.

One of the advantages of a largely unsupervised childhood—my parents had bigger fish to fry—is that I was not saddled until adolescence with the self-hatred and body shame that seems, even today, to afflict most girls. As far as I knew, at ten I had no gender, and so was free until at thirteen I began to be treated as “just a girl” to join these mock-heroic combats on equal terms with all of the knights.

All I lacked was the armor, the shield, and the spear.

A little later, it began to occur to me that knightly combat was no longer a part of reality, if it ever was. Heartbroken, I went to my mother to complain that the days of chivalry were over and gone. She must have been surprised.

Thoughts on chivalry: Going to the post office just this week I encountered a younger African American man kindly holding the door for me with consideration and respect long enough for me to walk through without hurrying.I smiled and thanked him and my thoughts was on chivalry.

*…thoughts were on chivalry.